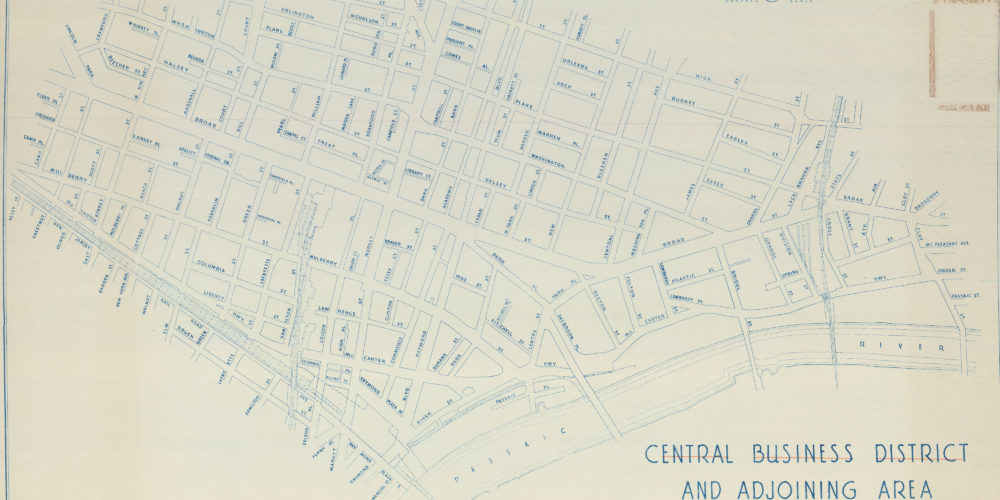

Image courtesy of Dana Library photo collection.

Rhythm 3 (Future) » Urban thresholdsRhythm 3 (Future)

Urban thresholds

Urban Thresholds (Text by Eva Giloi, Oct. 1, 2019)

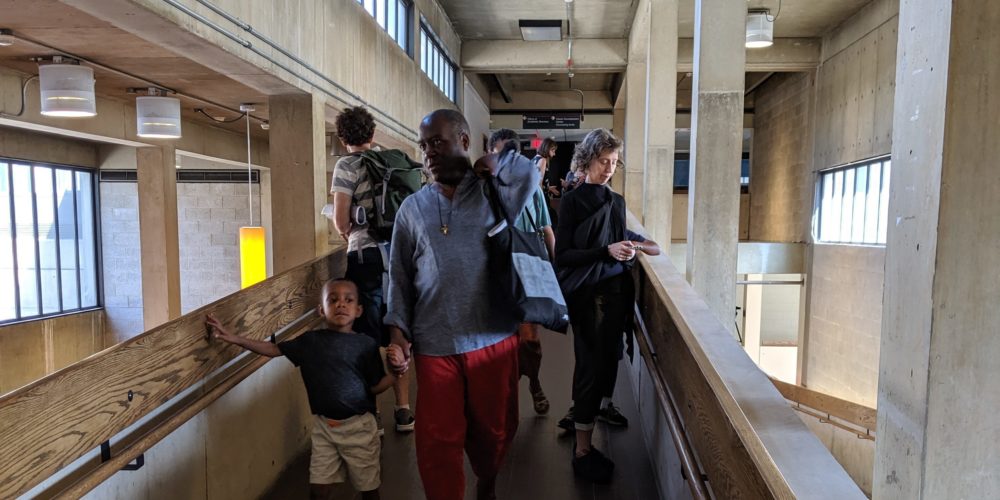

Spatial theorists speak of thresholds – doorways, windows, gates, corridors – as demarcating boundaries of access and affect: who gets to go where (and when), and the emotions that accompany the transition from one space to another. As individuals move between spaces, they also move from one interior state to another. This transfer can be highly ritualized, as in rites of passage, or more mundane, for instance in the domestic interior when children are allowed into the parents’ ‘master bedroom’ under certain conditions. Those conditions may be more or less well-defined, but the boundary to the space is clearly marked by the doorway and the open or shut door. The same holds true in the urban space for gated communities, for instance, which mark access and feelings of inclusion/protection vs. exclusion/exposure.

The existing literature on thresholds tends to study visibly marked structures with intentional meaning, like the gate or the doorway. This project goes beyond overtly structural thresholds to study “urban thresholds” created through the phenomenological/sensory experience of space, in the embodied process of moving through a city. It focuses on how affective thresholds allow access for some pedestrians and not for others, creating emotional communities and perceptions of “place” as a space of meaning. In fostering belonging, urban thresholds produce atmospheres of sanctuary, nostalgia, and immunity from threat. In enforcing exclusion, dominant groups use the experience of space to question the legitimacy of those who do not belong. Urban thresholds are also often ephemeral and implied: even though the physical space of the city is open to those moving in it, urban thresholds create sensory boundaries and affective barriers.

These boundaries can present themselves in various forms from above and below, in the official and alternate use of pathways and routes; body language and modes of physical behavior in the public space; traffic ordinances, quality of living laws, regulations on disturbance of the peace; habits of comportment, shaming of non-conformist movement or behavior, or marking certain habits of movement in class-based terms (for instance reactions to a street corner culture); soundscapes and how sound works to create walls and boundaries; odors as thresholds, marking ethnic neighborhoods, the worth and value of property, and their connection to zoning policies; or the relationship between social networks and paths of movement.