Rhythm 3 (Future) » Research AbstractsRhythm 3 (Future)

Research Abstracts

A Brief History of Urban Renewal in Newark

Excerpts from Making a Place: Rhythms, Ruptures and Rutgers in 1960s Newark

Changes in Newark

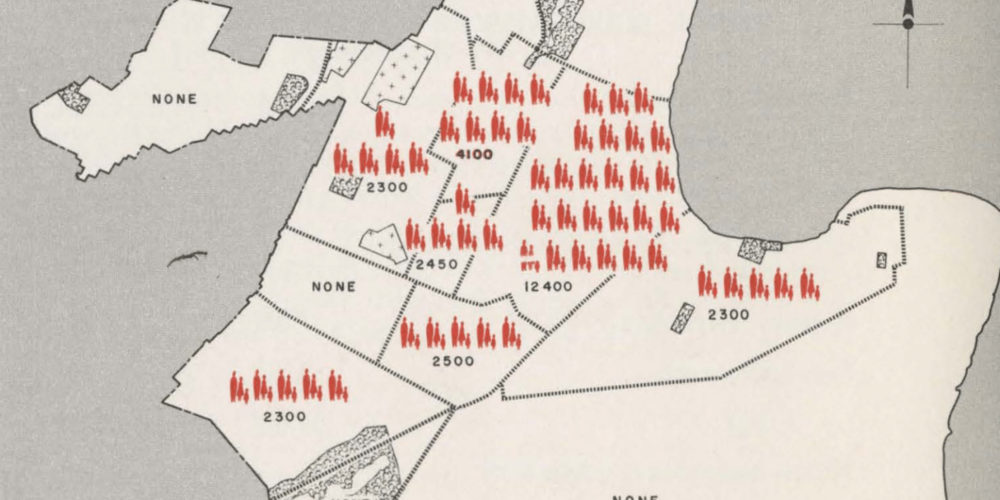

In the nineteenth century, Newark became an industrial hub producing a wide range of manufactured goods. The city’s population grew in tandem with its industry, from 136,500 in 1880 to 500,000 in the 1920s. The city gained Southern and Eastern European immigrants around 1900, joined by a fast-growing population of Italians. In 1880, the city census showed 407 Italians living in the city. By 1911, that number had risen to 50,000. Newark’s Jewish community also numbered nearly 50,000. In the mid-twentieth century, the Great Migration brought 6 million African-Americans to the North, including to Newark. In 1930, African-Americans made up 8.9% of Newark’s population. By 1960, that figure had risen to 34%.

After 1945, the GI Bill and federal mortgage policies reversed the influx by encouraging white middle-class families to leave for the suburbs, without making the same subsidies available to African-Americans and other minority groups. At the same time, the Federal Housing Administration redlined inner city Newark, marking it as unsafe for mortgage guarantees or investment. In Newark, as in many other US cities, these racialized incentives, combined with existing racial biases, resulted in a simultaneous “white flight” out of the inner city core and an isolation of African-Americans in declining housing stock in the inner city neighborhoods.

By then, industry and light manufacturing had also begun to leave the city in search of cheaper land and cheaper labor, whether on the urban periphery, in the countryside, or further away in the South and abroad. Not only did the wartime spike in production slow after 1945, but the federal tax structure encouraged manufacturers to build factories in outlying areas rather than refurbish existing facilities inside the city. In the 1950s, the population of Newark decreased by 92,000 people as suburbanization advanced.

History of Rutgers University-Newark

Rutgers was designated the State University of New Jersey in 1945. A year later, it acquired the University of Newark, with its Law School, School of Business Administration, and College of Arts and Sciences. The College of Pharmacy and College of Nursing joined Rutgers in Newark by 1952.

By 1946, the University of Newark had long since outgrown its space in the old Ballantine Brewery: its classrooms had sloping floors originally designed to drain off the brewery’s malt residue, and its library was so cramped that students used the Newark Public Library as a study hall. To accommodate its growing student body, the university rented space in 28 other buildings, including the old Marlin Razor Blade factory, the Eagle Fire Insurance building, and various homes on Washington Park.

As it looked to expand out from its rented buildings, the university had to raise funds where it could, especially after voters rejected a state bond issue for higher education in 1948. For the rest of the 1950s, the university set its sights on building a Law Center and Library. With Newark as the primary center for law in New Jersey, Rutgers’ Law Library promised to become one of the best in the country—if it weren’t for its lack of space. Hoping that the Law Center’s service to the state and legal aid work would help to raise funds in the private sector, Rutgers emphasized its role in producing “well-trained, morally secure lawyers” with “high regard for ethical ideals,” critical to “a free society.” The university’s fundraising efforts failed, however.

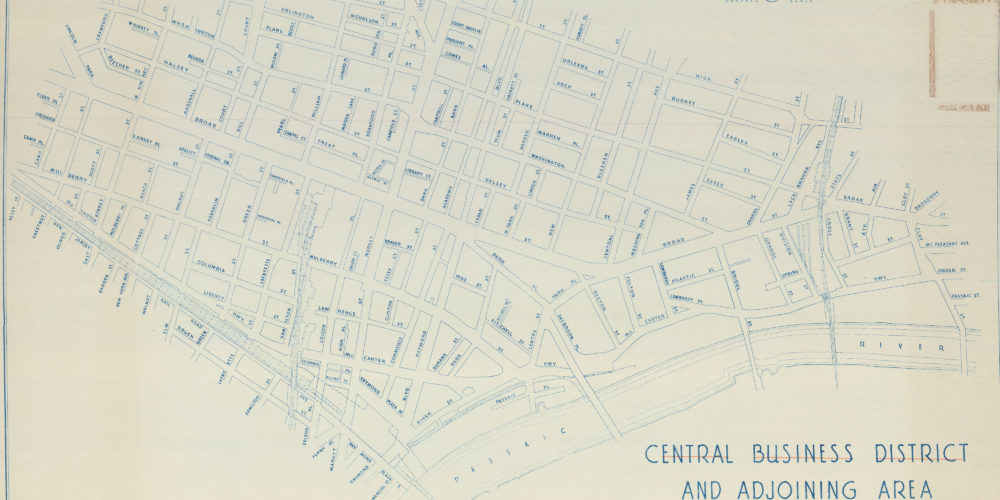

Rutgers was one among several cultural institutions that Danzig hoped would expand their presence in the Central Ward, including the Newark College of Engineering (now NJIT), the Newark Museum, the Newark Public Library, and Seton Hall University. Danzig’s goal was to rebrand the inner city core as a “cultural center” to draw developers into the Central Ward, but at a high cost to people living in the neighborhood. In the Central Ward and the Ironbound, 14,400 dwellings were slated to be cleared as part of Newark’s urban renewal plans. Although the Central Ward represented only 14% of all dwellings in Newark, it faced 40% of the planned relocations.

Renewal and Ruptures

Louis Danzig, the Executive Director of the Newark Housing Authority, had particular reasons for wanting to draw Rutgers into his redevelopment plan for the Central Ward, due to the way that federal funding and private development worked. Once land was designated as “blighted” by the Newark Central Planning Board, the Newark Housing Authority was free to purchase it with funds from the Federal Housing Authority. After clearing the land of its existing structures, the Authority could either build public housing or sell the land to private developers. Developers were reluctant to build in “slum” areas, however, thinking they would not be able to rent or sell the apartments easily. The Federal Housing Administration refused to provide mortgages to areas at risk of default, as part of its redlining practices: literally outlining poor-risk neighborhoods with red ink. Redlining had a distinctly racial cast: many of these neighborhoods were considered a poor risk because they were populated by African-Americans and other racial minorities. By drawing cultural and educational institutions into urban renewal territory, Danzig hoped to alleviate investor fears and attract funds to redevelop these contested areas.

Urban renewal plans cut across the fabric of existing neighborhoods, however, breaking up active networks and communities as the housing stock was cleared out. Many of the demolished houses were substandard, lacking indoor plumbing and running hot water, or in an otherwise physically dangerous condition. They often stood next to other homes, however, that were in better shape and only required rehabilitation rather than demolition. For most of the 1960s, urban renewal policies rejected selective rehabilitation in favor of large-scale clearance and the redevelopment of entire neighborhoods. From 1959 to 1967, 12,000 African-American families in the city center were displaced by land clearance to make room for public housing and highway construction. Families that were displaced by “slum clearance” were promised apartments in the Newark Housing Authorities’ public housing projects, but many were not accommodated.

The planning and construction of the Newark campus contributed to the benefits and hardships of urban renewal. To build the campus, Rutgers purchased seven blocks of land from the City of Newark, representing roughly 20 acres. 600 families were displaced as a result of the demolition required for the campus, without gaining access to the opportunities for mobility offered by higher education. African-Americans made up 85% of the population in the Central Ward, where the campus was located, but even in 1968 only 3% of students at the university were African-American. Within the Central Business District, Puerto Ricans made up 33% of the population but had a very small presence on campus, as did the Portuguese and Brazilian community living in the Ironbound. In the following decades, Rutgers University-Newark would institute measures to increase its diversity, ultimately becoming the most diverse college campus in the country.