Rhythm 3 (Future) » A Pragmatic View of Urban RenewalRhythm 3 (Future)

A Pragmatic View of Urban Renewal

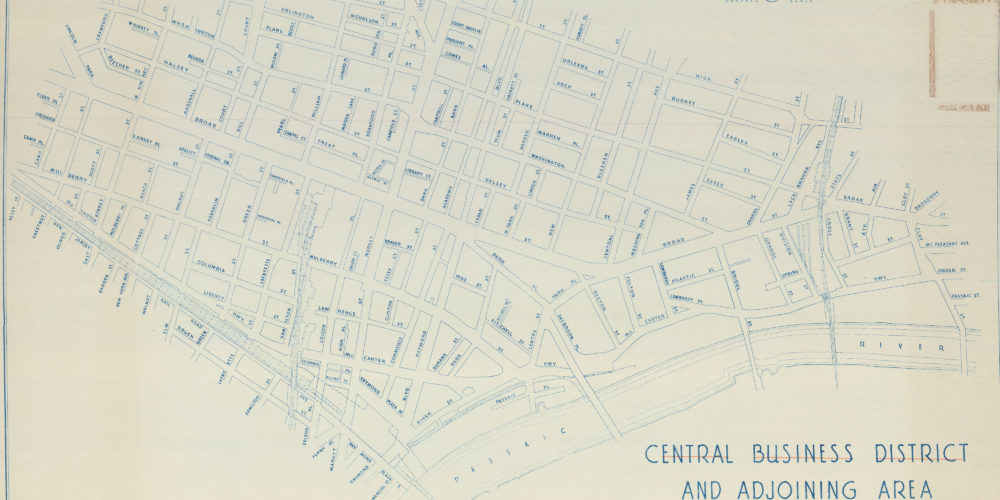

Urban renewal is a process that focuses on cleaning up and rehabilitating impoverished parts of a city. Newark, New Jersey, was one of the many cities that used urban renewal to revive their urban centers after World War II. Responding to the Housing Act of 1949, the Newark Planning Board and Newark Housing Authority created a series of comprehensive plans focused on removing blight from the city. They did so in an era of red-lining and other federal racialized policies that promoted segregation and blocked social and physical mobility for African-Americans and other minorities. Was Newark's Central Planning Board in the 1960s focused on improving living viability and refreshing the city for all its residents, or was the true aim of the Central Planning Board and the Newark Housing Authority to extinguish all parts of the city it did not accept or welcome? In earlier decades, the discourse around renewal was open about the dislocation that would come with urban renewal. Newark’s Master Plan of 1947 admitted that the city would struggle to support extensive revitalization without financial assistance. This would mean attracting people who could afford higher taxes to support the city, including private developers. In the 1960s, however, the Newark Housing Authority and Central Planning Board softened that tone and made it sound like they were making a better city for everyone by focusing on the dangers of blight to city residents. What the plans did not emphasize was the way that site feasibility was used to define areas targeted as ‘blighted,’ making them available for clearance, and that these sites in the inner city were primarily inhabited by minority groups and African-Americans in particular. Nor did the official documents admit that private redevelopers were largely interested in blighted areas because it gave them access to sizeable amounts of condemned land all at once, and that the Central Planning Board therefore had an incentive to find a way to evacuate large amounts of substandard dwellings in order to draw in private redevelopers. Was this merely an oversight or an intentional and racial strategy to remove people they didn’t want in the city?

To answer this question, this paper looks at the publications of Louis Danzig, head of the Newark Housing Authority, and George Oberlander, the city’s head planning officer, and compares and contrasts those with the publications of Dorothy Cronheim, director of the Newark Commissions for Conservation and Rehabilitation. While Danzig and Oberlander emphasized that the threat of blight was so overwhelming that large areas of existing neighborhoods had to be cleared, which meant breaking up neighborhood networks and moving thousands of families by force, Cronheim showed that the goal of creating a thriving Newark could be met by selective rehabilitation and conservation of existing homes. By focusing on better code enforcement, Cronheim concentrated on methods that would help prevent blight in the future and preserve buildings that did not require full replacement. Like her contemporary Jane Jacobs, who resisted Robert Moses’ massive urban renewal plans that would have destroyed the neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan, Cronheim gave an alternative to Danzig and Oberlander’s bid to turn Newark over to redevelopers in order to draw white suburbanites back into the city. Cronheim’s more subtle approach of rehabilitation and conservation had major potential to keep the neighborhoods intact, which helps indicate that the Newark Housing Authority was not committed to making a better city for all of its residents, but instead wanted both to create a new population and extinguish the existing one.

Abstract by Chelsea Rager

cmr425@scarletmail.rutgers.edu

Posted 9/9/2021